Charles Joseph and Sophie La Trobe, accompanied by their two year old daughter, Agnes, arrived in Sydney in July 1839. La Trobe had none of the training and experience which usually qualified a man for such an important administrative role. The typical colonial governor had a naval or military background. Charles Joseph’s experience was radically different. He was a refined and sensitive man who had spent years as a dilettante, imbibing all that was cultural and learned. After some weeks being tutored for his role by the Governor of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps, the La Trobe family took two weeks to reach Melbourne on 30 September, 1839 having encountered ferocious gales in Bass Strait en route. The following morning, he was rowed ashore to Liardet’s beach where he landed on the beach and walked into town in incessant rain for a first unofficial view of his new domain. The weather on 2 October was so bad that passengers were unable to go ashore. However, his diary entry for 3 October notes: ‘Landed with family 1 p.m.’

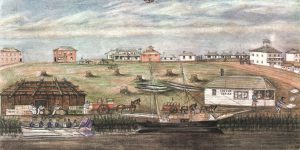

He found that Collins Street was the only street worthy of the name, while Elizabeth Street followed a frequently-flooded creek bed, and Flinders Street was little better than a bog. The water supply for Melbourne was, in the four years of settlement, increasingly inadequate and polluted from the discharge of tanneries and other industries. There was no town council to take care of local affairs. No development could take place without revenue being allotted by the government in far-off Sydney. The only building of note was the gaol.

What an amazing contrast this embryonic city must have presented to a sophisticated man who was accustomed to the elegance and size of London, Baltimore and Neuchâtel! Melbourne in 1839 was only four years old, with a population of approximately three thousand free settlers where, as La Trobe soon discovered, ‘the arts and sciences are unborn’.

Not only did La Trobe have to equip himself with all the requirements for life in a remote country, he also had to bring with him from England a prefabricated house, considered by some to be ‘in the chalet style’, which he had erected on the extremity of the town and named Jolimont.

It was evident on the day of his arrival in Melbourne that La Trobe was eagerly anticipated by the local population who expected him to act quickly on their desire for separation from the controlling powers in Sydney. He was hailed as ‘the patriotic founder of a new State’, but what they didn’t recognize was that La Trobe would, at all costs, do his duty by the Colonial Office in London.

In spite of, or perhaps, because of his tragic experience of witnessing the North American ‘Indian tribes melting like snow from before the steady march of the white’, La Trobe subscribed to the current Colonial Office policy of ‘civilising’ Indigenous populations. He saw his direction as attempting to bring Christianity to the Indigenous people of Port Phillip, but all attempts to urge them to give up their freedom and to conform to European requirements failed. More…

La Trobe’s perceived slowness to act on the question of Port Phillip separation from New South Wales was totally misunderstood by those clamouring for it. He, in the meantime, was pursuing it cautiously but vigorously, believing constantly that the timing of its adoption was an all-important matter. He had recognised soon after his arrival what a handicap being part of the greater New South Wales was for progress in Port Phillip. Separation when it eventually came in 1851 was a great achievement for La Trobe and cause for universal celebration in the new colony of Victoria, of which he became Lieutenant-Govenor.

Early Life Lieutenant Governor Later Life A Reflection The Artist The Botanist La Trobe Letters Family Tree Timeline La Trobe Sites Podcast Video