No sooner had the advance news of separation been received, and at the same time the new bridge – the second bridge – over the Yarra River officially opened, than the single most revolutionary and momentous event in the history of the colony occurred. Gold in enormous quantities was discovered, creating the dominant and most far-reaching issue of La Trobe’s many years in Victoria.

No sooner had the advance news of separation been received, and at the same time the new bridge – the second bridge – over the Yarra River officially opened, than the single most revolutionary and momentous event in the history of the colony occurred. Gold in enormous quantities was discovered, creating the dominant and most far-reaching issue of La Trobe’s many years in Victoria.

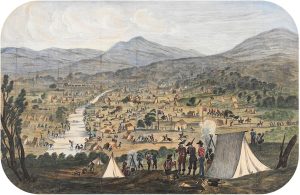

He visited the gold fields on horseback on several occasions to observe at first hand the conditions of the miners. The licence fee, which he had introduced at 30 shillings per month as a source of government revenue, was not a successful venture. It alienated the diggers who, more often than not, had not been successful in their search for gold and who were, therefore, unable to pay. Inexplicably, La Trobe doubled the cost in January 1852 to three pounds a month, but thought better of this increase soon after as the anger of the diggers reached a peak. So unpopular was La Trobe over the exorbitant licence fees, and so many were the government proclamations bearing his name, that the approach of the licence inspectors on the gold fields was signalled by cries of ‘Charlie Joe’ or ‘Joe’ to alert the unprepared. He was described by the Geelong Advertiser ‘Our Victorian Czar’, a dictator imposing an unrealistic and impossible tax when no goldfield in 1851 had yet proven its worth.

A deputation, principally from the Bendigo goldfield, met La Trobe in his office in August 1853 with a petition signed by 5,000 miners demanding reduced licence fees and civil rights. The meeting was not a success. La Trobe responded defensively and coldly to each of the clauses put forward. The moment of meeting with the miners could have changed history. Had La Trobe been able to act differently, perhaps the tragedy of Eureka would have been averted. But La Trobe could not put himself in the miners’ shoes, and he was fearful of anarchy on the goldfields. In fact, it could be said that La Trobe panicked before ‘the mob’. The time was not there for him to deliberate. He had to make decisions, quick decisions, and these were sometimes the wrong decisions.

The historian Geoffrey Serle, in his definitive study of the gold rush, came to the conclusion that, when faced with the appalling difficulties of the times, La Trobe had tried to ‘govern chaos on a scale to which there are few or no parallels in British colonial history’. He had, in fact, managed to keep the colony for which he was responsible operating in circumstances ‘in which the archangel Gabriel might have been found wanting’.

The constant demands and the criticism of his every move or lack of action made him seek an alternative to the daily tediousness and harassment of life in Melbourne. In his years as administrator of the colony, La Trobe made ninety-four major horse-back rides through country Victoria, as far afield as Mt Gambier in the west and deep into Gippsland in the east, which he carefully documented in his private diary.

La Trobe was an explorer who charted routes, notably to Gippsland, to investigate a report of coal deposits, and to Cape Otway where, after two abortive attempts, he personally blazed the trail to, and was responsible for the erection of, the essential light house on that dangerous rocky promontory.

Well aware of his increasing unpopularity, despite his considerable successes, La Trobe submitted his resignation on 31 December 1852. He was suffering from stress induced by his long service in this often difficult colony and was concerned for Sophie whose health was far from robust. His resignation was accepted, but his successor, Governor Sir Charles Hotham, did not relieve him until June 1854. In the meantime, Sophie and their children travelled to England and then to Switzerland where she died in January 1854. Sadly, La Trobe was to read of her death in a newspaper which arrived in Melbourne before he was notified by letter from the family.

On 5 May 1854, very nearly fifteen years after his arrival, La Trobe himself left Melbourne for London on the trans-Pacific route aboard the modern steamer, the ‘Golden Age’, and then went on to Switzerland to reclaim his children who were being cared for by their aunt and grandmother.

Early Life Superintendent Later Life A Reflection The Artist The Botanist La Trobe Letters Family Tree Timeline La Trobe Sites Podcast Video